Ashish Kumar last saw his brother Vinod when he was being driven away by a senior police officer in Ludhiana, in northern India.

Vinod’s body was never found but the CBI, India’s intelligence agency, believes that the officer, Sumedh Singh Saini, was responsible for his death.

They filed murder charges against him within a month. That was in 1994.

Twenty-two years have passed since the murder case began. Only three of 36 witnesses have been heard so far. Four witnesses have already died without being presented in court.

At 94 years old, Vinod’s mother, Amar Kaur, cannot hear or speak well. She does not seem to understand much about life at present. But when she hears her son’s name, she yells at the top of her voice, “Insaaf!”, which means justice.

Kaur, who used to go to court on a stretcher, gave her testimony in the murder case when she was aged 86, 14 years after her son went missing.

She asked the court several times to hear her statement sooner, fearing that she did not have long to live. When she was finally heard, the judge had to step down from the podium and stand next to the witness box to be able to hear her thin, fading voice. But before she could finish, he decided to break for lunch. The next available date for her to deliver her statement was a month later.

In the time that has passed since Vinod disappeared, Saini has continued in his role and was promoted to director general of police in Punjab. He still has charges hanging over him.

Vinod’s family on the other hand, have had to leave their family home, give up their business, and move to Delhi. They claim to have been threatened on numerous occasions and moved in order to remain safe and follow the case.

Vinod’s murder case is not exceptional in India.

More than 22m cases are currently pending in India’s district courts. Six million of those have lasted longer than five years. Another 4.5m are waiting to be heard in the high courts and more than 60,000 in the supreme court, according to the most recently available government data. These figures are increasing according to the decennial reports.

Last week, Tirath Singh Thakur, the chief justice of India’s supreme court, broke down while addressing the prime minister, Narendra Modi, as he lamented government inaction over judicial delays, particularly for failing to appoint enough judges to deal with the huge backlog of pending cases.

In the government’s budget for 2016, only 0.2% of the total budget was given to the law ministry, one of the lowest proportions in the world.

“There is a systematic problem with India’s courts,” Vinod’s younger brother Ashish says. “And because of it our family has suffered so much.”

The number of cases, however, is only a part of the problem. Take a walk through any court building in India and you’ll see long queues of people waiting outside courtrooms without any guarantee of getting a complete hearing.

India has one of the world’s lowest ratios of judges to population in the world, with only 13 judges for every million people, compared with 50 in developed nations. As a result, scores of cases are heard every day, which leads to a large number of adjournments, judges passing cases between them, and increasingly long queues of people waiting outside courtrooms on the off-chance that their case is heard.

“Judges are under enormous pressure,” Mukul Mudgal, a former high court judge, says. “You have around 30 or 40 cases every day, and usually, you spend an hour before court reading the files. I used to do half of them the previous night. It’s a lot of work, and it is chimerical to hope that any judge will read every page of every case he’s dealing with.”

Judges are paid little compared with lawyers, which has led to a steady decline in the calibre of those hearing cases.

To add to the burden, lawyers frequently use delaying tactics such as routinely appealing against verdicts, or saying they are sick or failing to show up in court.

“Adjournments are given freely, witnesses don’t come on time, and there’s nobody looking at judicial administration,” says Harish Narasappa, whose thinktank Daksh analyses data on judicial delays.

“If you go to court and ask the judge for an adjournment, the judge will ask ‘OK, what day do you want?’ At that time, neither the judge nor the lawyer has any clue what the judge’s capacity is for that day next week. What’s the point of saying ‘I’ll hear you on this day next week’ if he just doesn’t have the time?”

Narasappa estimates that the delays cost India’s economy trillions of rupees every year.

Major Manjit Rajain had to miss a day of work every month for nine years over a case against him that was eventually dismissed as a clerical error.

After he retired from the army and opened his first business, the registrar of companies filed a suit against him for misrepresenting himself because his army files showed his surname to be Rajan, without the i, and he had written his surname Rajain, with an i, on the forms to register his company.

Rajain explains how trivial the error was. Even though the former soldier showed the court his passport, birth certificate, marriage certificate and several other documents to prove there was an ‘i’ in his last name, the case against him was not dismissed for nine years.

“The good thing that came out of it,” Rajain says, “was that I made friends with many major businessmen sitting outside the courtroom, because they had all been dragged there for equally trivial reasons.”

“This country’s progress depends on a strong judicial system which can provide quick justice in commercial matters,” says Dushyant Dave, a senior advocate in the supreme court, who believes the judicial system has deteriorated since he began practicing in 1978.

“We need foreign investment to improve technology and capital. If we’re not able to protect technology in terms of intellectual property rights, and if we’re going to drag investors into our court system for several decades, then they’re not going to come.

“We have more than 700 million people living in poverty, and this is the greatest challenge of our democracy. The judiciary has a great role to play. Unfortunately, I don’t think the judiciary really realises that.”

The legal logjam has led to overcrowded prisons, with more than 68% of the prison population still on remand. Some prisons are more than two or three times over capacity. Getting bail usually depends on the quality of a defendant’s lawyers.

“In criminal trials, the process itself is a punishment. Many under-trial prisoners end up doing their entire sentence without getting a full trial,” says Alok Prasanna, an analyst from the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a thinktank.

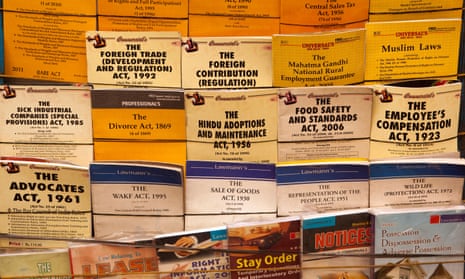

The result of these never-ending cases is a crisis of faith in the legal system. Two-thirds of ongoing cases are criminal rather than civil cases, which suggests that India’s judicial system more than six decades after independence is not much different from the one inherited from the British Raj, where rulers used the legal system as a means of maintaining order and criminalising agitators, while the majority of civil disputes were settled outside court.

“Parties don’t see litigation as a way to resolve disputes so much as get what they want by making the other party suffer and come to court repeatedly for years,” Prasanna says.

“I always tell people who approach me for legal advice not to go through the courts, because you may win or lose the case, but you will definitely lose both your money and your sanity.”

Attempts to improve the system have seen little success. After the horrific gang rape of a medical student in Delhi, a series of fast-track courts were set up to speed up cases concerning violence against women. It has not made much of a difference – more than 93% of rape cases are still awaiting trial as trivial matters hold up the progress of cases.

Asha* was gang raped in 2005, when she was 13. Until 2013, the court was simply trying to decide whether one of the men accused of raping her should be tried as a juvenile or an adult.

Even after her case was fast-tracked, it took two years for the court to sentence the man who arranged the gang rape.

Her friend, who cannot be identified for legal reasons, says: “Her entire childhood has been eaten away by this trauma. The man is now married and has children and has even run for election. No one will marry Asha or her younger sister because of what happened to her.”

Her lawyer says that he is certain the man will appeal against the verdict. “Why would you not appeal?” he says, over the phone. “It’s a way out.”

In the absence of speedy justice, vigilantism thrives. Groups defending women’s rights such as the Gulabi Gang or the Love Commandos are infamous for taking their revenge in cases of domestic violence and so-called “honour” killings. Corruption too, is endemic. People would rather bribe a police officer or a judge than go through the lengthy hassle of a trial.

Meanwhile, the impunity that criminals may enjoy because of how slowly the legal system operates, is exemplified by India’s elected politicians. One in three politicians in the Indian parliament have criminal records, with the vast majority of those involving serious cases such as rape, murder or kidnapping.

Prasanna says that even the most basic needs of the courts are not met. “Some courts are having to hold sessions in the dark because there’s no electricity. Old buildings need to be maintained. People need to be trained better, even when computers are provided people are not trained to use them.”

Dave believes that the judicial system is in dire need of a complete overhaul. Laws need rewriting. Judicial process needs to be streamlined. Lawyers need to be penalised for delaying matters without reason. “The government is not interested,” he says. “No politician or bureaucrat wants a strong judiciary.”

Mudgal agrees, but doesn’t believe the changes needed to strengthen the judiciary will come in his lifetime.

In the meantime, Ashish Kumar will keep fighting for his brother. “I believe in this country, and I believe I will get justice one day,” he says. “My brother was a great man. That’s why I’ve spent my entire life trying to get justice for my brother. The rest is up to God.”

A request was made to talk to the lawyers for Sumedh Singh Saini in preparation of this article but no response was forthcoming.

* Her name has been changed to protect her identity.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion